Are you funding predominantly white organizations to do racial justice work?

Over the past decade plus, as philanthropy recognized that so many existing institutional leaders in various sectors needed to increase their focus on racial equity, resources often flowed to support predominantly white organizations to diversify their staff and focus.

In some cases, as racial equity became more palatable and “trendy,” largely white organizations have been funded to create projects that move others in their field.

Often the initial motivations to get many of these organizations to focus on race was the desire for reform, changing sources of money (moving existing resources), or simply the recognition that in order to be vital and relevant they needed to be more responsive to changing demographics. However, as funders have greater willingness to fund racial equity, there has been concern that they are more apt to fund change in the often predominantly white organizations with whom they’re already familiar, rather than change the way they are funding to trust more organizations led by people of color.

Although it is critical that racial justice work is carried out across racial and ethnic groups, including white communities, the amount of resources that have gone to shifting majority white-led organizations taking on racial equity work has the impact of compounding existing inequities.

What we mean by “predominantly white organization”

By predominantly white, we mean grantseekers whose decision-makers are majority white, which, depending on the organization’s structure, could mean board members or executive staff. We do not conflate this definition with having a white CEO—there are organizations with CEOs of color that operate without a racial justice commitment. We also exempt from this discussion white groups that deliberately organize other white people to participate in racial justice struggles, which is work that was recognized as critical by both activists and funders in our research.

Problematic Historical Patterns

According to funders and activists we interviewed, one consequence of diversity and inclusion framing is that energy and money are directed toward predominantly white organizations to take on racial justice projects, including internal diversification efforts and externally facing program work. These grants may fund outreach to people of color, internal training, or an advocacy project related to structural racism, among other things.

There are two common rationales for such investment: first, that as a result of white organizations waking up, communities of color can access and use the power and resources of these white groups to build their own organizations. Second, that groups of color don’t have the capacity to accept large grants or start a new body of work, so the engagement of a white group is required.

The negative effects of such entry reshape the political and cultural landscape that undermines the goal of building capacity and infrastructure that is owned and operated by people of color. These effects include:

- Lowered standards and unearned credibility for white organizations that put wrong frames out into the world that gain traction because of their access to media and social capital, or whose good work fails to credit adequately the people and organizations of color that helped make it so.

- A drain on the capacity of leaders and organizations of color whose work the white organization uses to create its own products. It is highly unlikely any predominantly white organization is proposing to conduct racial justice work without seeking guidance and input from organizations, intermediaries, and leaders of color that have been working, sometimes for decades, to build their base of people, knowledge, and legitimacy.

- White organizations that focus entirely on internal diversity efforts, but have no commitment

to changing their strategy and program for racial justice goals, or—as we also see—the exact opposite: white organizations creating external products, but not addressing their own demographics and internal power relations. - Unchanged relationships, or even a growing gap between people of color working on racial groups and the funders who become interested in that work. Grants to white organizations can further consolidate their access to funders while continuing to shut out groups of color that can’t get a meeting.

Whose Power and Capacity Are You Trying to Grow?

Funding white-led, mostly white organizations is not the same as directly supporting and building the power of grassroots groups led by and for communities of color, especially when viewed through a racial justice lens.

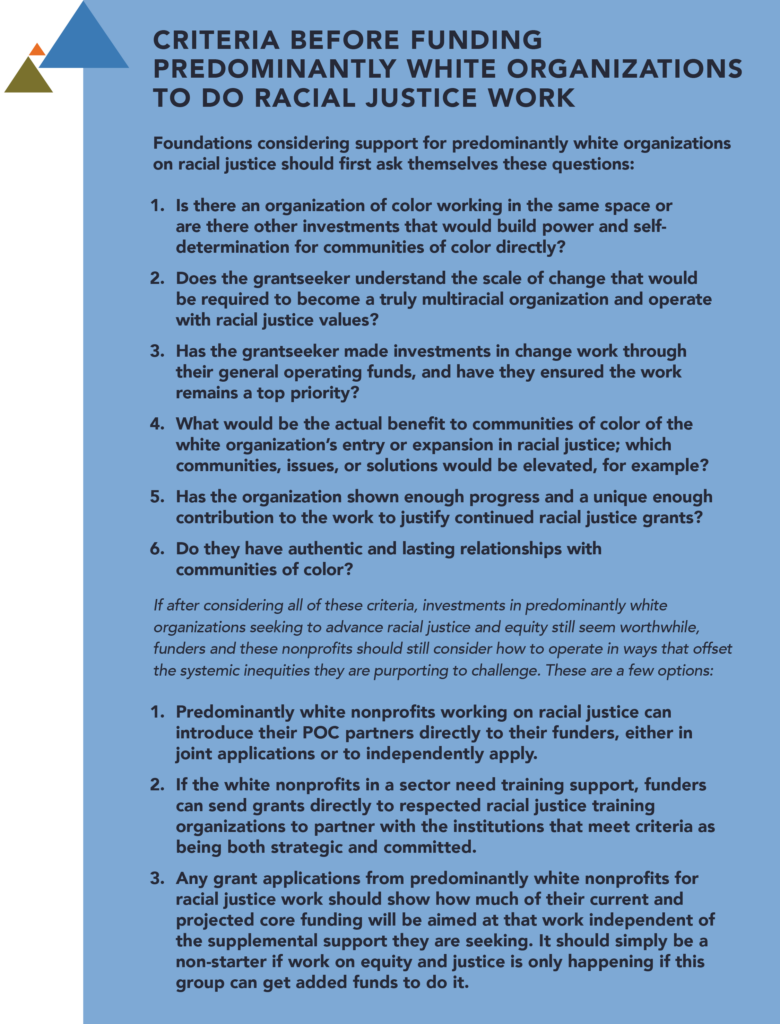

A power-building approach to racial justice means that the goal of our grantmaking has to be self-determination and agency among communities of color themselves. Therefore, funding of predominantly white organizations to carry out racial justice work has to be contingent on rigorous criteria—far more rigorous than what racial justice leaders are observing and experiencing as common practice.

Grantmakers can’t afford to overlook the unique strengths and capacity of Black- and other people of color-led nonprofits to effectively and creatively identify a sustainable and just roadmap to securing a thriving future for all.

So before funding organizations with primarily white decision-makers for racial justice, answer these 6 critical questions from the Grantmaking with a Racial Justice Lens: A Practical Guide (see pages 26-29).

Grantmaking with a Racial Justice Lens centers what racial justice activists want funders to know. In addition to examining the cost of funding predominantly white organizations, it features experienced funders’ stories and how-to tips on advancing foundation practices to achieve racial justice such as:

- Responding to internal resistance

- Determining positive and negative consequences of using philanthropic intermediaries for your sustained racial justice

- Correcting the course of some problematic trends in racial equity and justice funding.

- And more!

Learn more about Grantmaking with a Racial Justice Lens: A Practical Guide