By Lori Villarosa

Peak Grantmaking, Journal | Issue 19 Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Feb. 1, 2022

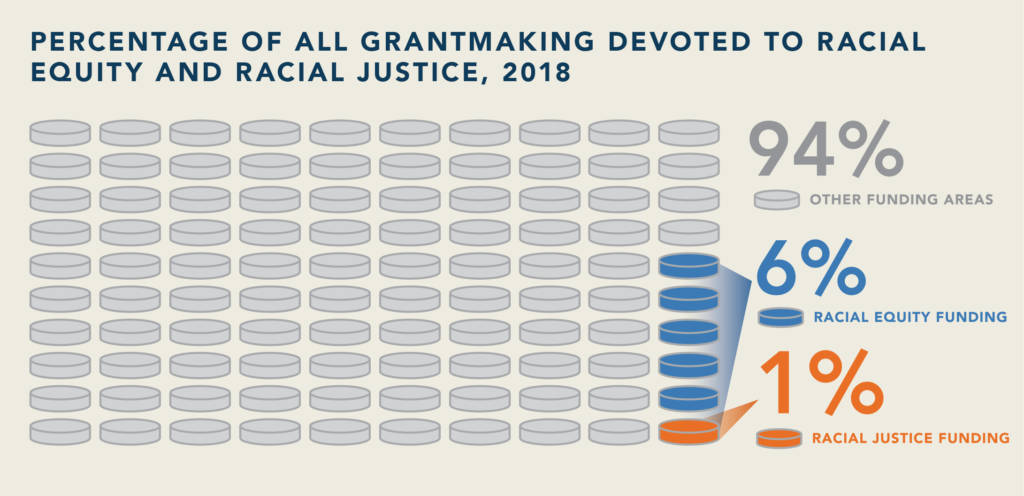

Grants management professionals are strategically positioned to influence a funder’s racial equity and racial justice funding. But in three decades of working in and with foundations, I have consistently seen a pattern where people serving in these roles are excluded from these conversations as a matter of institutional habit. As a result, there is a lack of understanding across the field about how the work of grants management directly relates to advancing racial equity and justice. Even when they are included, the scope of their influence can oftentimes be limited to paperwork, reporting, and only the most technical aspects of the grantmaking process. And yet, they also have the ability to shift what is and isn’t funded, understand what funder pushback might arise, and how grants are understood and reported.

But before I get into how grants managers can impact racial equity and racial justice grantmaking, it’s important to first define these frequently conflated terms and then examine the current racial equity and racial justice landscape.

Racial equity and racial justice defined

Long-standing tensions driven by unequal power dynamics have shaped debates over how racial equity and racial justice are defined and who does the defining, and there has often been little shared understanding of these terms across the philanthropic field. In our work with foundations and movement leaders, we at the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE) have seen these tension points manifested within hundreds of foundations. But through our work, we also have the benefit of lessons from movement leaders and change agents, and these have inspired some recommendations that we think will help grants management professionals strengthen their own roles in advancing racial justice work.

Over the past three years, organizers for racial justice and racial equity have called for more precise definitions of those terms, in part reacting to the conflation of equity with diversity and inclusion work. That conflation has muddied the distinction between aiming for change within existing systems and aiming to transform those systems as a whole.

Funding with a racial equity lens has four key features:

- Analyzes data and information about race and ethnicity

- Understands disparities and the reasons they exist

- Looks at structural, root causes of problems

- Names race explicitly when talking about problems and solutions

Racial equity focuses on the prevention of harm and the redistribution of benefits within existing systems. Racial equity projects don’t usually attempt to fundamentally transform the systems that generate suffering, but they do address the unfair distribution of pain. Ensuring that as many people of color as possible have collective access to the systems that produce education, employment, housing, and a clean environment is vital.

Racial justice funding encompasses the above features, but adds four more critical elements:

- Understands and acknowledges racial history

- Creates a shared, affirmative vision of a fair and inclusive society

- Focuses explicitly on building civic, cultural, economic, and political power by those most impacted

- Emphasizes transformative solutions that impact multiple systems

Racial justice adds dimensions of power building and setting transformative goals, and explicitly seeks to generate enough power among disenfranchised people to change the fundamental rules of society. Power building includes recruitment, leadership development, people-oriented and people-guided education, alliance building, strategic communications, and the deployment of a variety of pressure tactics, from protests to lawsuits. To change the fundamental rules means that a core dynamic of the system is fixed, added, or removed, shifting the balance of power between the community and key institutions such as government and business. Power building can even include providing social services or support for the arts—two sectors traditionally separated from civic power in philanthropy—if they are clearly and effectively attached to racial justice goals and strategies.